It is interesting to see how countries with a long trade history have gradually developed and implemented phytosanitary regulations in response to perceived risk and incidents. This is why I like very much the story of the stem rust and the barberry bush. This was the first recorded attempt to control and legislate a disease. It started like this:

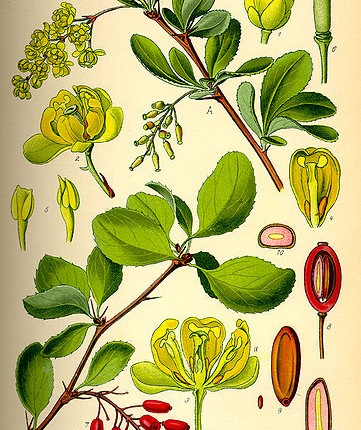

In the mid-1600s, Rouen (France) was the first town to put in place legislative measures to control barberry bushes because farmers had noticed that black stem rust was much worse in fields surrounded by hedges including barberry bushes. Nobody knew at the time that barberries (Berberis vulgaris) were an alternate host in the stem rust life cycle (Puccinia graminis), but people had noticed a link between the presence of the barberry bushes in hedges and a greater impact of the disease on their cereals. So a law was passed requiring that barberry bushes be destroyed in wheat growing areas. This was the first evidence of a coordinated eradication and control. Later on in the late 1700s, other countries including Germany and the USA adopted the same law in hope to control stem rust on their cereals.

It was only in 1865 that a famous mycologist, Anton de Bary, discovered the complete life cycle of the stem rust and demonstrated that indeed barberry bushes play an essential role in the disease cycle. Without this alternate host, Puccinia graminis could not complete its life cycle or conjugate to produce new strains. So it made sense to eradicate barberry bushes to control the rust. Following this discovery, many other European countries made the eradication of barberries mandatory, and some had great successes in controlling the rust.

Problem solved, it seemed…

However, soon after, it was discovered in the USA that the stem rust could use another set of alternate hosts in another genus all together (Mahonia). Consequently, the US Department of Agriculture prohibited the import of all Barberry and Mahonia species.

But it did not stop there: in the late 1900s, it was reported that the eradication of barberry bushes had little impact on stem rust in warmer climates. In Australia and in the Southern parts of the USA, the stem rust could overwinter on local grasses and winter cereals. So the rust had found another way to survive from one season to the next. It was also found that air-borne rust spores could travel great distances and be transported by wind currents to reach cooler climates and infect cereals even in barberry-free areas. This is why some cooler countries only had some relative success with their barberry eradication programs.

So it was not all due to the presence of alternate hosts after all. There were other ways the rust could spread or overwinter. We learnt the hard way.

This story demonstrates why it is essential to understand the biology of an organism before developing strategies to regulate or control it. It is now the foundation of WTO-SPS agreements that no measures should be implemented if there is no solid and sound scientific evidence to underpin them.

One Comment

John West says:

January 17, 2014 at 5:23 am

For blog 1 I do recall that another exercise in futility was a US forest Service summer project for high school kids to attempt to eradicate Ribes (wild currents and gooseberries) the alternate host for white pine (Pinus monticola) blister rust (Cronartium ribicola) in big forests of the Pacific Northwest. Summer pay for hard work slogging through the underbrush of minimal benefit in protecting the white pine.

Cronartium was invasive to Europe and North America from Asia back in the early 1800s. In the USA it probably succeeded somewhat in the East. In the West, however, the Ribes species proved too evasive, difficult to kill and resilient, and the approach was abandoned.

John